The Last Act of the Tragedy

What now followed drove the Gottscheers into a thicket of barely concealed force and unmitigated terror. A "Jahrhundertbuch" cannot disregard the last years they spent in the old Ortenburgian primeval forest fief because somewhere someone does not like to be reminded of the assaults on freedom, on human dignity and on human rights in Gottschee, or because this period is associated with National Socialism. These assaults took place on three levels. The conscientious historian likewise does not ask himself if he wishes to suppress, to gloss over, or to manipulate what the Slovenes did to the Gottscheers, what the Slovenes endured from the German Reich, and finally what the Gottscheers themselves undertook to survive. On the contrary, he is obliged to depict the decline of the linguistic island of Gottschee as dispassionately, if not uncritically, as possible.

Even if one twists and turns the developments, events, and decisions of the personalities and institutions that were involved, Gottschee is incessantly drawn into the tragic entanglement from which there is no escape. Everything that the Gottscheers do from now on is wrong.

The state government in Ljubljana soon tightened the reins. The "Schwäbisch-Deutsche Kulturbund", the cultural organization of the Germans in Yugoslavia, had also established several district groups in Gottschee. This organization was forbidden. Thus, the Gottscheer youth were also denied the legal foundation for their cultural work. The prohibition was based on the observations of the security force that young Gottscheers associated with young Germans from the Reich. Volker Dick, a priest son from Freiburg in the Breisgau, was one of these young Germans who was in Gottschee in the summer of 1933 as a philology student. At first he concentrated on the dialect and traveled throughout the "Ländchen" to study it. He often talked to the farmers, also to the young people, and collected material for his work. In so doing, he noticed that not linguistic discussion but rather new economic ideas were needed here. Without being asked or commissioned to do so by any office or organization in Germany, he made it his personal objective to get the youth interested in this.

Schwabish-German Kulturbund, Gottschee, 1940

Already on his next visit he presented a "Aufbauplan" (development plan) for discussion. It was to halt any farther economic and cultural decline due to emigration, oppression, and demoralization of the people. Dick found many willing listeners among the rural youth, and some among the district leaders in the city.

The "Volksgruppenführung" (district leadership) was not a public institution that was created through elections or appointments. Instead, there were at its head two men whose opinions one listened to because of their personalities and who at times also carried out official duties: attorney Dr. Hans Arko from the city of Gottschee and the church counselor Josef Eppich, priest in Mitterdorf. As of 1927, Reverend Eppich was also the elected representative of the Gottscheer voters to the "Gebietsausschuß" - more or less the equivalent of the provincial legislature in Austria. From the outset it was realistically not possible for him to do anything for his "electorate". Dr. Arko was a temporary deputy district leader of the "Staatspartei" (state party) decreed by King Alexander I. in 1929. Compared to the party system in the Federal Republic of Germany and in Austria, it is the equivalent of the Christian-Socialists, the Austrian Peoples' Party, that is, a liberal-democratic party.

Religious Councilor Josef Eppich, Reverend August Schauer, 1930

In view of the hard line the Slovenes were taking towards the linguistic island, the two men feared that the young people would outwardly imitate the Hitler Youth in their cultural work. The first signs were already evident in 1934. Arko and Eppich, despite their bad experiences after 1918, still adhered to the basic principle of loyalty to the state and the nation. The expected activity of the young people came and could apparently not be stopped. To be sure, in its essence and in its cultural work, it was true to the Gottscheer character. The club nights, the

topics for conversation and discussion, even the singing were directed towards preserving the traditions of the homeland. German hiking songs and the snappy songs of the German youth in the Reich were sung on camping and hiking trips, but more and more songs in the dialect were also unearthed because they had the true Gottscheer folksong character and were not a product of the hectic thirties. They were composed by the young farmer's son Peter Wittine from Rieg.

In 1935 something seemingly insignificant occurred. Willi Lampeter from Mitterdorf was expelled from the secondary school, in the city of Gottschee. His principal was of the opinion that, as a student at a Slovenian secondary school, he had too actively supported German national matters, even though he was a Gottscheer by birth. This expulsion challenged Lampeter to become even more nationalistic. Within a few months he was considered the spokesman of the Gottscheer youth, who gradually made it known that they considered themselves solely responsible for the future of Gottschee and who strove to relieve the old leadership at the appropriate time. In fairness it must be pointed out that the call for a new spiritual and economic direction within the framework of the Gottscheer traditions did not come first from the young, who reacted to the powerful impulses from without. The Gottscheer Kalender (almanac) of 1931, which was published by the Reverend August Schauer in Nesseltal and whose content he controlled, stated: "The Gottscheer farmer must again cast his glance towards the homeland. He again has to have confidence in his land and has to be shaken from his lethargy by taking the Gottscheer agriculture out of its present isolation and organizing production and marketing on a co-operative basis". To be sure, the "Aufbauplan" (development plan) first clearly stated how this was to be done.

The project that Volker Dick discussed with the young people proceeded logically from the fact that there were too few workers left (for reasons which are known to us) who could adjust the sharply lowered standard of living to the increased demands while still using the old farming methods. Beyond this - and this was always strongly emphasized - the "Aufbauplan" was to provide an economic incentive to stay in the homeland.

Let us take a look once more at the fateful circle of events which led to the enormous calamity that was intensified by the world-wide economic crisis. Because of the shortage of farmhands, the Gottscheer farmer had neglected to clear the land continually, particularly the pastures and hills that were higher up. Feed stock declined and, as a result, the livestock also declined considerably. Less milk and fertilizer were the result. Less fertilizer meant a lower crop yield and a decrease in the area that was planted. Conclusion: Emigration continued to increase.

The "Aufbauplan" simply reversed this decline: renewed clearing of the pastures and meadows = more livestock = more milk and calves = more fertilizer = more planting fields = general increase in farm production. The plan also included the introduction of high-yield fruit trees and the better care of them, as well as the use of the fruit harvest in the production of sweet cider. Experts for this endeavor were brought in from Germany. The tourist trade was also to be developed systematically. To this end, promising meetings were held with a German travel

agency. The first noteworthy tourist attraction was a secure path built by the youth in the idyllic woodland village of Pogorelz. Another accomplishment of the young people in the voluntary workforce was the securing of the hiking trail from Morobitz to the Krempe, the most beautiful lookout in Gottschee into the cavernous Kulpa valley and the mountains of Croatia. They also built a skihut near Altfriesach and, as a finishing touch, the youth of the Oberland built a clubhouse in Mitterdorf. They were bitterly disappointed. On the eve of the dedication of the clubhouse,

they held a torchlight parade through Mitterdorf, for which a permit had been filed with the authorities. This parade was brutally stopped by Slovenian youths who had been brought in from outside. Armed with sticks, pickets, clubs, and other "tools," they jumped out of the dark and struck down women and children. The police who were present did not intervene. The Gottscheers, not prepared for such an attack, could not defend themselves at all. Even before the men could strike back, the phantoms had again disappeared in the dark.

Two cooperative arrangements, enclosed pastures and a modern dairy, both new for the "Ländchen", were to provide the farmers with a steady and guaranteed income. A model enclosed pasture, again the voluntary joint effort of the youth, was set up in the village district of Hohenegg / Katzendorf. A plan for a dairy suited to the needs of the Gottscheer farmer was drawn up. To give a steady side-income to the girls and women as well, one went back to old types of cottage industries. Of course, wood carving, the oldest form of Gottscheer cottage industry, was revived. An expert from Germany was also on hand for these undertakings. To create a market for these products, a cooperative was founded in the city of Gottschee in 1936 which handled their sale in Germany. The siblings Hilde and Herbert Erker from Mitterdorf, Sophie Kren from Ort, as well as the siblings Olga and Hans Spreitzer from Pöllandl, were particularly active in the cottage industries in the linguistic island itself. In addition, Herbert and Hilde Erker revived the singing of old German and Gottscheer songs at numerous club meetings.

|

|

|

| New costumes | Costume head covering | Knittings |

The proper functioning of farming was, however, a prerequisite for the flourishing of the in part totally new economic base. Discussions and good advice alone did not suffice. One needed practical examples, showing how it is to be done and - money! But where was one to get it? Only one thing was for certain. One could not expect the Yugoslavian government to provide financial assistance.

Dr. Hans Arko came to the rescue with another tradition-bound idea. He suggested that one apply to the Reich for a renewal of the peddler permit first granted by Emperor Frederick III. in the year 1492. This would allow the traditional peddler trade of the Gottscheers to flourish once more in a form and number that was appropriate to the time. Due to Dick's efforts the economic ministry of the Reich agreed to it and processed it through the internal administration. As a trial, several dozen selected farmers were sent to Germany during the winter of 1934- 35 to introduce the peddler trade. In general, the experiment was a success. The peddling was carried out in the manner in which it was described in detail in this book in the chapter on the nineteenth century. In the three winters from 1935-36 to 1937-38, about 300 men were allowed to peddle in each season. They were sent individually and in groups of various sizes to those cities which were deemed suitable for this exceptional undertaking. Thus, for example, fifteen men worked in Munich, two in Dessau/Anhalt, and one in Schwäbisch-Gmünd. The peddlers wore their traditional dress (see illustration). At first they were advised and looked after by students, then beginning with the 1935-36 season, by members of the VDA ("Volksbund für das Deutschtum im Ausland" - national organization for German culture in foreign countries).

|

|

| Gottscheer peddler | Donation badge, Verein für das Deutschtum im Ausland (VDA), comrade sacrifice Gottschee, 1934/1939. |

The men from the linguistic island belonged to the "Gottschee-Hilfswerk" (relief association) which had an office in the city of Gottschee and in Dessau / Anhalt. The latter office was moved to Berlin in 1938. In Gottschee, Dr. Arko

set up an office at his attorney's bureau and employed someone to handle the correspondence and the bookkeeping. It is quite unusual for Gottschee that a woman, Mrs. Paula Suchadobnik from the city of Gottschee, was the business manager of this arrangement that was exclusively for men.

The peddlers from Gottschee had to give part of their net profits to the organization for the peddler trade and to the hardship fund from which losses were to be reimbursed. While still in Gottschee, the applicant had to pledge that he would purposefully invest his surplus in his own farm. In addition, he had to sign a statement that he would return home and not stay in Germany at the end of the season. In general, the profits ranged from a few hundred to several thousand marks. Because of the regulation of foreign exchange, the peddlers could not transfer their earnings directly through the postal service or the bank but were paid through the Savings and Loan Bank in Gottschee.

The surplus from the "hardship fund", which hardly ever had to be used, was allocated for the construction of the dairy. The plans for its construction and the network of twenty-two cream-skimming stations were completed in 1938. The plans were to be put into effect in 1943.

What, however, was the situation as far as the practical models were concerned? Dick suggested that new farmers, that is, sons of farmers, be sent to Germany for agricultural training. Willie Lampeter from Mitterdorf and Martin Sturm from Loschin made this idea a reality. By 1937 the two young men had become the undisputed leaders of the farming youth. Whoever took a closer look could see that Lampeter had acquired a disciplined following. The young men whom he now sent to Germany for the agricultural training were of this circle. Volker Dick also prepared the way for them. The training in modern agricultural production methods took place on the Rauhen Alb, where the climate and the soil were similar to that found in Gottschee. They spent the summer of 1937 working on farms selected for this purpose. Afterwards Willi Lampeter gathered the sixty men at a "Winterschule" (winter school). Its purpose was to give the future model farmers the theoretical means for their roles as agricultural leaders.

Because of these activities - related to Gottschee - Dr. Arko and Reverend Eppich found themselves in a difficult political situation domestically. On the one hand, they watched with satisfaction the efforts of the young people to secure the future of Gottschee. On the other hand, experience had shown them that the Yugoslavian authorities would not let them be. Thirdly, since the young people no longer allowed anyone to interfere, the two "old men" attempted to take counteractive measures on the cultural front at least and thus - perhaps! - still rescue something. On August 13, 1935, Dr. Arko gave the new Yugoslavian Prime Minister, Dr. Milan Stojadinavic, a memorandum with the request that at least the remaining German school divisions be allowed to remain and that the German teachers they required be approved. He submitted the same memorandum to the provincial government in Ljubljana in October 1935. The latter only replied in the fall of 1936 that it could not do anything for Gottschee as long as Slovenes are being denationalized in Carinthia. Thereupon Reverend Eppich undertook steps in Vienna and Klagenfurt to bring about the equal treatment of the Slovenian minority in Carinthia and in Gottschee. The Slovenes in Carinthia were offered full cultural autonomy, but the head of the provincial government in Ljubljana

did not even want to listen to a Gottscheer delegation. He explained his negative stance by stating that the provincial government is not the appropriate authority for this. Here again the whole Slovenian conception of things related to Gottschee once more became evident. The governor claimed he was not responsible for the minority rights of the Gottscheers but was responsible for those of the Slovenes in Carinthia. In his own country he thus only felt authorized to exterminate the Gottscheers.

Jugoslavian Prime Minister Stojadinovic

Dr. Arko did not receive any answer at all from Prime Minister Stojadinovic. In world politics he had the reputation of being sympathetic to the German. Thus, it is possible that he was involved in loosening the reins in the summer of 1935 that had been placed on the "Schwäbisch-Deutschen Kulturbund" (Swabian-German cultural organization).

The proclamation of a "Grundverkehrsgesetz" (property disposal law) in June 1936 proved that the authorities in Ljubljana had also extended their intention to eliminate the linguistic island of Gottschee to the economic sector. It stated that every change in property ownership within a 50-kilometer zone along the national border had to be approved by the war, that is internal affairs, ministry. This law did not yet threaten the existence of Gottschee even though it was within the 50-kilometer zone. But the instructions for its execution which were already

issued in December left no doubt about it. It called for a commission that was to check every case to see if the change in ownership was in the interest of the state or not. In other words, a change of property ownership among Gottscheers was now impossible. Its intention was soon revealed by the reality. Gottscheer properties that became available could be bought by Slovenes for next to nothing. The Slovenian youth organizations "Sokol" and "Orjuna" underscored the measures of the authorities with verbal threats, the most tasteless of which stated: "We

will pave the main square in Gottschee with your skulls."

The legal uncertainty reached ever newer heights. Dr. Michitsch sketches them as follows in the Cultural Supplement No. 58 of the Gottscheer Zeitung:

"Legal uncertainty, the lack of legal protection against the misuse of judgment, the absence of an internal government authority that could have been called upon in cases of infractions against minority rights, the discrimination against the ethnic minority through the arbitrary issuance of laws and decrees which were totally forbidden according to international and national laws." The exercise of this "legal status", the resistance against this system of oppression, grew especially among the young people. They had looked for and found a way of halting the further economic decline, because they saw it as their legitimate human right not to stand by idly as their homeland was being destroyed by political powers. They also found a way of bringing about at least a makeshift cultural balance. An invisible struggle for the dialect and the written German language had set in. Wherever it was possible, the few priests gave young and old instruction in the German language. Hundreds of primers appeared and were passed from hand to hand.

Secondary School councilor Hermann Petschauer, Mayor Franz Lusser, Dr. Viktor Michitsch.

In the years 1936 and 1937 dissatisfaction with the old leadership grew. It was accused of doing too little to secure the basic rights and the cultural demands of the Gottscheers. The young people thought that they themselves could force a change in the national Yugoslavian minority policies in Gottschee by making their voices heard. In 1938 Lampeter felt that the time had come for him to take over the leadership of the ethnic group. To be sure, he proceeded from a decisive false assumption: Without expressing it, he expected the German Reich officially to support the decidedly goal-oriented appearance of a young ethnic group leadership against the Yugoslavian state. To be sure, this seemed to be the case in one instance. In November 1938, Dr. Hans Arko was notified by the "Arbeitsstelle" Gottschee (employment office for Gottschee) in the VDA, Berlin, that he was relieved of his leadership of the ethnic group. It was easy to guess what had prompted this letter. In Gottschee one accused the deposed leader of nepotism in the selection of peddlers. Embittered, the attorney resigned. He had not even been given the opportunity to resign voluntarily in an appropriate manner. The religious adviser in Mitterdorf, however, did not wait for his turn. On January 1, 1939 he handed over the editorship of the Gottscheer Zeitung to a young man, the professional journalist Herbert Erker. He had received his journalistic training at the Deutschen Volksblatt, the daily newspaper of the Germans in Yugoslavia, in Neusarz (Novi sad), whose chief editor was the Gottscheer Dr. Franz Perz from Mitterdorf.

A three-member panel consisting of the businessman Josef Schober (city of Gottschee), Willi Lampeter, and Martin Sturm was set up. Schober took over as chairman and was then known as "Volksgruppenführer" (ethnic group leader). Until then he had hardly been heard of in public life. In actuality, it was soon to become apparent that the still youthful Lampeter (born in 1919) simply used the much older man as a front. Lampeter's followers, however, felt their views, intentions, and achievements were confirmed by the new development.

One of the first undertakings of the new leadership panel was to deliver a declaration of allegiance to the German consul in Ljubljana. Among other things, it stated that the Gottscheers were prepared to accept directives from the Reich. Transferred to the political reality, this was not intended to mean that they wanted to relinquish their native traditions. To be sure, they sympathized with the "renewers" in the Danube-Swabian region without, however, unconditionally agreeing with their political views. "The Gottscheer leadership had very definite political ideas", the then nineteen-year-old youth leader in Gottschee, Richard Lackner, explained to the author in 1973 in a conversation about the thirties. He continued: "We knew that we could not, in any case, influence the general political and governmental changes, and that our entire concept was based on the fact that we were a linguistic island in the Yugoslavian kingdom, that our actions must be based on this situation in order to prevent the decline, the destruction of Gottschee." In spite of the declaration of allegiance and the professed programmatic inclusion in the straits of world politics, the new leadership internally reserved for itself a certain degree of freedom to act. It is still evident in the words of Richard Lackner in 1973: "... because we wanted to do things on our own based on very independent thinking and an independent view. We wanted to create that type of Gottscheer who was prepared to participate in the renewal of his homeland."

Berlin, September 1, 1939. Hitler attacks Poland. Three weeks later: The Republic of Poland no longer exists.

|

|

|

| Battleship "Schleswig-Holstein" bombards the "Westerplatte" near Danzig |

German soldiers on the Polish border |

Hitler

announces the invasion of Poland, 1.09.1939 |

Berlin, October 6, 1939. In a speech delivered at the Reichstag, Hitler announces that he thinks it necessary to relocate the ethnic groups in Europe so that the boundaries between the nations can be more clearly defined. The German nation would withdraw its outposts. That he was serious about this became clear the following day. He named the Reichsführer SS, Heinrich Himmler, to be the "Reich's Commissioner for the Consolidation of the German Peoples". Himmler's new assignment was not so new anymore, as was shown by the relocation of the people of South Tyrol, which had been planned for some time. The relocation agreement with Italy went into effect in June of 1939. Thus, the negotiations must have begun months before. The Italian and German relocation offices were set up in South Tyrol in August and September 1939.

The German ethnic groups in eastern and southeastern Europe panicked. The panic in Yugoslavia forced the German delegate in Belgrade to make the unfortunately worded declaration in the Deutschen Volksblatt (German newspaper in Yugoslavia) that the relocation of the Germans in Yugoslavia was "not under immediate consideration."

Heinrich Himmler (1900-1945), one of the chiefly responsible for the murder of millions of European Jews

By being named "Reich's Commissioner for the Consolidation of the German Peoples," Heinrich Himmler's power had increased considerably. He set up a "Stabshauptamt" (staff headquarters) in Berlin to administer this new assignment and put Ulrich Greifelt, the brigade commander at that time, in charge of it. The ethnic political organizations in the Reich were also put under the jurisdiction of the Reich's commissioner, especially the "Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle" (VOMI) (an intermediary office for ethnic German matters), which had been part of the

"Staff of Deputies of the Führer," and the "Volksbund für das Deutschtum im Ausland" (VDA) (ethnic organization for Germans outside of Germany). Despite its subordination to the VOMI, the latter had still maintained a certain degree of autonomy as the cultural caretaker of Germans with foreign citizenships. Now one no longer sought to consolidate this ethnic group.

Understandably, the Gottscheers too were very much affected by Hitler's announcement. Rumors spread from village to village; no one knew anything definite. The leadership of the linguistic island was silent. Outwardly, it acted as if there were not going to be any resettlement. The permission for establishing the "Kulturbund" (cultural organization) was a surprise and was given without imposing any restrictions. This seemed to support the position of the leadership. The Yugoslavian government granted its permission by stating that concessions had been made to the Slovenes in Carinthia. Within a few weeks, twenty-five village chapters of the "Kulturbund" were founded, including even villages which previously did not have any.

This permission for the "Kulturbund" allowed Willi Lampeter to initiate a plan he had been thinking about for some time. In the fall of 1939 he set up the "Gottscheer Mannschaft" (team). The charter of the "Kulturbund" was changed for this purpose so that every member between the ages of 18 and 50 was automatically a member of the "Mannschaft." Lampeter assumed the position of "Mannschaftsführer" (team leader). In the village chapters, the leaders of the team divisions were called "Sturmführer." Lively cultural activities were very soon in evidence. Disciplined compulsory exercises patterned after the organizations in the German Reich were part of them.

This histrionic, almost hectic activity - while at the same time remaining silent about the resettlement - did not, however, mean that the inner circle of Gottscheer leaders avoided a discussion of the question: to resettle or not to resettle? It was quite aware that the Gottscheers now found themselves not only facing two fires but three. First, they were still faced with the extermination efforts of the Slovenes. Second, they believed that they had found a way that would enable them to fight for their survival and culture on their own soil until a permanent

favorable solution to the Gottschee problem was found. Third, however, it was precisely that political power which alone had the ability to bring about such a solution that wanted to transplant them somewhere else. What could the Gottscheers do? What were they allowed to do?

The young men who were the leaders and who still could not have had any political experience were at a loss.

All discussions ended in the same dead-end: There was no way out except to resettle. The circle around Lampeter thought that if the resettlement could not be avoided, then they would at least be able to influence its objectives. They decided to present their wishes and opinions to the nearest available German official, to the German consul in Ljubljana. This took place on November 6, 1939, four weeks after Hitler's speech. Frensing reports the conversation and comments on it on page 25 of his book about the resettlement of the Gottscheers as follows:

"They already made the decisive concession on point one. Also, in the matter of resettlement, the interests of the ethnic group are to be subordinate to the interests of the nation as a whole. Based on this, subsequent considerations of the Gottscheers became very relative and, bluntly expressed, were reduced to the point

where they were almost insignificant. The Gottscheers were dangerously deluding themselves when they thought that once their views on the matter had been heard they could then change Hitler's basic views on foreign and resettlement policies according to their own ideas in a concrete, historical situation. Viewed from the national-socialistic perspective, it must thus have seemed downright heretical that the Gottscheers found an incontestable decision by the "Führer" to be inadequate for an eventual resettlement. According to the leadership of the ethnic group, the fact that Gottschee is part of the Italian sphere of interest is not sufficient reason for resettlement. The reference of the Gottscheers to the German-Russian pact as proof that relationships between different powers can change very suddenly and completely surely gave rise to embarrassing jokes."

Further on Frensing continues: "It was the desire of the Gottscheer leadership to be "annexed" to the Reich in case the south-Slavic state collapsed. This was already apparent among the ethnic Germans in Slovenia during the March 1939 unrest when they openly demanded annexation after the occupation of the "Resttschechoslowakei" (rest of Czechoslovakia).

One member of the Gottscheer leadership had even sent a telegram to Hitler from Graz on April 13, 1939 in which he requested Anschluß (annexation).

It expressed concern about the incorporation of Gottschee by Italy, which had just attacked Albania."

The Gottscheer farmers and city dwellers also heard nothing about these discussions in Ljubljana. The internal political pressure grew steadily in the linguistic island. The possibly unavoidable resettlement pushed all other topics into the background. In the meantime, however, the number of opponents to the resettlement also grew.

The "Stürme" (local groups) were developed. The rural police and the Slovenian nationalists repeatedly assumed a menacing stance at Gottscheer functions. A small little volume entitled "Die Wirtschaftsfragen des Gottscheer Bauern" (The Economic Issues Concerning the Gottscheer Farmer) written by Willi Lampeter and Martin Sturm appeared in this tension-filled atmosphere of 1940. It had the effect of a small, consoling promise for the future because it contained many a good suggestion for the Gottscheer farm.

The Gottscheers, this time including the leadership, heard nothing about what transpired behind the scenes in the Reich's capital. For example, the head of the ethnic German intermediary bureau, SS-Obergruppenführer Werner Lorenz, made a notation on June 27, 1940 that "in case war broke out between Germany and Yugoslavia, parts of southern Styria and Upper Carniola were to be annexed to the 'German Reich,' but not those of Gottschee." Lorenz, too, thought that Gottschee obviously belonged to the Italian sphere of interest and hence demanded the resettlement of its inhabitants (Frensing, p. 26). He surely did not express his own thoughts in this. And still one more thing in the remark is noteworthy: The Obergruppenführer was already aware in June of 1940 of a military conflict with Yugoslavia.

SS-Obergruppenführer Werner Lorenz - SS General

In the meantime, the "Heim-ins-Reich-Bewegung" (Back-to-the-Homeland Movement) had been proclaimed and initiated. The affected ethnic groups were told as little about the actual reasons as the German people themselves. Hitler had announced the withdrawal of the German "outposts" on October 6, 1939, not to redraw the European boundaries but out of purely power and nationalpolitical considerations. He and Himmler wanted much more to adjust the biological deficit which was facing the German nation. Demographers, above all Dr. Friedrich Burgdörfer, at that time president of the Bavarian state office of statistics, had already precisely pre-calculated in the twenties that the German population would visibly decline in the 1970's because the nearly two million men who had died in World War I and their unborn descendants were missing in the German population pyramid. The two most powerful men of the Third Reich also included in their calculations that the Second World War would result in additional heavy losses and that the deficit of 1914-1918 would be considerably increased. On the other hand, the territories of the former Hapsburg monarchy - including the German minority in Czechoslovakia - contained the valuable human potential of about ten million. The Germans from Czechoslovakia had already been incorporated into the National Federation in 1940; the Germans in the Baltic provinces had also been included in the Reich. Only the Germans in Yugoslavia, Hungary, and Rumania - all together again about 2.5 million - still awaited resettlement into the Reich. Essentially, these Diaspora-Germans were the descendants of settlers who had become established in their settlement regions in widely spaced periods of colonization: the Transylvanians (1140-1160) and the Danube-Swabians in the southern Hungarian lowlands during the reign of Maria Theresa (1740-1780).

From the behavior of those in power in the Third Reich towards the national political command situation in Himmler's surroundings one can easily deduce that they really were serious about also taking in these southern European ethnic Germans to make up for the biological deficit. On the one hand, it was stated that one did not want to let these Germans perish as cultural fertilizer for other nations. What a contradiction to the power consciousness in the "Reichskanzlei" (state chancery) in Berlin! As if the "Großdeutsche Reich" (the extended German Reich), which viewed itself as the greatest military power in Europe for infinity, had to ask any other government for permission if it had wanted to support the ethnic Germans within its borders. And, on the other hand, all commands and

directives concerning the "Festigung Deutschen Volkstums" (consolidation of German peoples) were very confidentially collected in 1939-40 in the staff headquarters of the main division "Menscheneinsatz" (manpower) under the direction of SS-Obersturmbannführer Dr. Fähndrich. Among other things, the publisher wrote in the introduction:

1. Those Germans living "outside of the sphere of interest of the larger German Reich" were to be resettled "according to urgency and necessity." They thus would be liberated "from their role as cultural fertilizer for foreign countries."

2. This call of the "Führer" indicated a "complete revolution in former German ethnic policies," because the until now "often romantically colored rapture that was enthusiastic about the dispersion of the Germans" had been changed according to the principle: "Taking in the valuable German blood to strengthen the Reich itself."

3. The "feeling of blood-relatedness to the German people as a whole," which the ethnic Germans had demonstrated, assured them of "at least a moral claim to a good reception in the Reich ... and to the availability of a sound livelihood."

4. Despite the loss of the old homeland, the Reich was, in comparison to the ethnic German, "to a much greater extent ... the giving part."

This obligated "the returning Germans to organically adapt themselves to the discipline, the drill and the order of the larger German Reich." To this end, Dr. Fähndrich made two concrete demands:

"When an ethnic group becomes part of the Reich, the former ethnic group organization ceases to exist, because the Reich stands above the ethnic group"

and

The concepts of Baltic-Germans, Volhynia-Germans, and Bessarabian-Germans, etc., on the contrary have to be exterminated as quickly as possible.

The Gottscheers, too, were to become very quickly acquainted with the above concept of the "Reich's Commissioner for Consolidation of the German Peoples." As we know from the above quoted comment in the documents of the SS-Obergruppenführer Lorenz, Hitler thought of conquering and dividing Yugoslavia militarily as early as the first half of 1940. The coup d'etat in Belgrade on March 27, 1941, which resulted in general devastation throughout the country, seemed to him to be a good opportunity to carry out this plan. On April 6, 1941, the German troops marched into the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and put the not very effective army out of commission in a few days. The German attack had taken them completely by surprise. Also the Gottscheers! What they feared set in. On April 20, 1941, the fragments of the south-Slavic state were "newly arranged." Mussolini had sent his foreign minister son-in-law, Count Galeazzo Ciano, to the conference. The Italians received Lower Carniola with the region of Ljubljana, the Reich kept Upper Carniola as a new part of the district of Carinthia, as well as Lower Styria which had been incorporated into the district of Styria and was administered from Marburg an der Drau. The Croatians were granted their own state, and Old Serbia was allowed to exist as an independent state.

Dictators - Fascist Mussolini and the National-Socialist Hitler. Incomparable suffering of the German, Italian and many other Nations of the world were the consequences of this political alliance.

The breaking apart of Yugoslavia was the prerequisite for conquering Rumania, which gave him free access to the Black Sea coast and the land base for an assault on the Soviet Union. Despite all the talk about the "steel axis Berlin-Rome," Hitler, by this Yugoslavian campaign, thus also prevented the Italians from conquering the Dalmatian Adriatic coast. The conquest of Albania and Greece was a clear signal that Mussolini intended to make Italy's claim to the "mare nostrum" a reality. In this intermezzo of so-called world politics, Hitler's willingness to give up all claims to South Tyrol suddenly takes on a different aspect, even small Gottschee takes on a new look for the German-Italian relationship. The dictator in Berlin sacrificed two pawns in his continental game of chess so as not to be disturbed by the dictator in Rome in his big move with the queen. When the latter, however, noticed that his friend on the other side of the Alps had outdone him, it was too late.

The Gottscheers, however, had to endure a war of nerves without comparison after Yugoslavia had been smashed apart. For days they were convinced that the German army would occupy the "Ländchen." The villages, through which the tanks passed on their way to the city, were bedecked with garlands. Lampeter's "Mannschaft" acted as if the army would approve of their activities as being reasonable and appropriate. The young men saw to it that law and order prevailed in the region. The district captain who was still in office was directed by the "Mannschaftsführer" to order the rural police to hand over their weapons to the "Stürme" (local groups). (Personal information from Richard Lackner.) In addition, the Gottscheers got back the weapons that had previously been taken from them, including hunting rifles. On April 13, 1941, Willi Lampeter then took over the administration of the district leader's office in Gottschee on his own authority. Compared to the administration of the German Federal Republic, this meant that he had appointed himself provisional district magistrate. His office was in the Castle of Auersperg in the city of Gottschee.

Hopes and expectations rose to a feverish restlessness as the advance of the army was delayed further and further. A delegation of Gottscheers hurried to Rudolfswerth (Novo mesto), where Hitler's troops supposedly had stopped. The German section commander received them cordially but declared that he had no orders to go beyond the line they had reached. Thus, it became clear to the delegation that it was located on the line of demarcation between the German and Italian areas of interest.

Instead of an advance division of the German army, the Gottscheers received the news from the "Reich's Commissioner for the Consolidation of the German Peoples" that the "ethnic group Gottschee" was to be resettled. As fate would have it, the news arrived on April 20, 1941, the day of the conference in Vienna. Three days later, a delegation from the linguistic island received Adolf Hitler's personal confirmation that he is giving the Gottscheers an "historic assignment" as "defense and border farmers." For the time being, however, Lampeter and his

circle kept Himmler's message about the resettlement and the content of the conversation with Hitler a secret. And while the "Führer" in Marburg an der Drau received the delegation from Gottschee, an Italian advance division moved into the city. Its first act was to remove Willi Lampeter from his office as district leader. He had held his office for only ten days. The dream of independence by the small ethnic island in the calciferous region had been dreamed to an end for the third and last time.

Adolf Hitler and the "Mannschaftsführer" (militia leader), Marburg / Maribor, 23.04.1941.

The Gottscheers were paralyzed with fear. The leadership was bombarded with questions. It dodged them with evasive explanations. Nothing was heard about Marburg, nothing about personal views. It did not even confirm that which everyone could conclude for himself after the Italians marched in, namely, the resettlement.

When? Where to?

The youth and those with political insight accepted the foreseeable fate. Many of those who had been peddlers in the years 1934-1938 thought of Germany as a possible destination for resettling, thought of "their" cities—perhaps they would be allowed to peddle for a few winters after the war so that they could build themselves a new home?

Now after several decades and not under the pressure of the events in the spring of 1941, it is easier to judge if the leadership of the Gottscheers acted responsibly or not. They thought they did, but today one is inclined to say that this question no longer even arises because the leadership could not have acted otherwise. One thing, of course, is certain: it used the wrong tone. But that was determined by the time. Some of the people thought the young people had led them by the nose. On the other hand, the leaders themselves had not been informed

about the details of the when and where to. Given these circumstances, one can, to a certain extent, understand that the leadership became nervous. Although it did not have to lead great masses, it nevertheless was, above all in human terms, certainly not an easy task to have to be the liquidator of a family enterprise that was centuries old and whose existence was being threatened by a large corporation due to no fault of its own. But the pros and cons of the resettlement were ever more passionately debated precisely because the leadership felt it had to remain silent. When the leadership realized that the "cons" were gaining, it reacted in a harsh tone: In the Gottscheer Zeitung of May 1, 1941 - note that not even four weeks had passed since the collapse of Yugoslavia - it attacked "the alarmists" with extremely dangerous-sounding threats. The leadership felt it had to document the independence of its decision-making not only to its own people but also to the Italian occupation forces. On May 2, 1941, the ethnic group leader Josef Schober appeared before the Italian high commissioner Emilio Grazioli in Ljubljana, handed him a declaration of allegiance to Mussolini, and presented the wishes and suggestions of the Gottscheers to the Fascist civilian administration of the province of Ljubljana. Signor Grazioli agreed to deal with all questions in consultation with the ethnic group. However, it was to become evident very soon that the high commissioner had not the slightest intention of asking the leadership of the ethnic group for its opinion or of perhaps even being guided by it. This was particularly true of the Italian view of the Slovenes.

In its efforts to appear independent from everyone, the leadership board Schober-Lampeter-Sturm also acted very self-assured in Berlin. The main office had "invited" it to a meeting set for the middle of May. One wanted to know in the capital of the Reich if the leadership of the ethnic group felt personally and organizationally capable of handling the resettlement. By presenting the Gottscheer Zeitung of May 8, 1941 - at that time the paper appeared weekly - it proved that they had already set up a leadership staff on their own. It stated:

The ethnic group leader has ordered that the following offices be established:

| A. | Ethnic

group leadership, administrative head of the ethnic group leaders

(Josef Schober), |

| B. | The

staff of the "Mannschaft," administrative head of the "Mannschaftsführer" -

Willi Lampeter, appointed for the economy - staff

leader Martin Sturm, for the nutrition program - Johann Schemitsch. |

| C. | Youth

leadership, administrative head of the youth leaders - Richard

Lackner, |

| D. | Office for Organization and Propaganda, administrative head - staff leader Alfred Busbach, appointed editor - Herbert Erker. |

To be sure, the resettlement is not yet mentioned in this directive of the ethnic group leader. According to the three-member board, the trip to Berlin was a total success, since the staff headquarters had approved of its suggestion to undertake the resettlement as soon as possible and to again settle the Gottscheers

as a unit. There were also no misgivings about the intentions to categorize those who were willing to resettle according to the following groupings and to treat these differently than the rest during the settlement phase: those who were in mixed marriages with Slovenes, those without property, those not suited to be farmers, and small property owners (later also "political unreliables"). Greifelt also agreed to let the ethnic group leadership carry out the resettlement on its own. Thus, the ethnic group leadership could assume it was authorized to prepare and

initiate the departure of the Gottscheers as they saw fit. This it then did. And only now, when it felt it had total freedom to act, did it fully confirm the tragedy that was befalling the Gottscheers. The following appeal to all Gottscheers, signed by Schober and Lampeter, appeared in No. 21 of the Gottscheer Zeitung on June 22, 1941:

"Gottscheer countrymen and countrywomen: The Führer calls us home into the Reich! Await his command with iron discipline! Let your work and industriousness show still in the last hour that you are worthy to be Adolf Hitler's Germans! Our efforts in the old homeland in 1941 shall show the world that we, as we did for 600 years, were able to inhabit the calciferous region also in the last year of our ethnic German testing period, and that we were able to extract from it our meager living. Present to our Italian ally a unique image of German manliness as an expression of our unyielding loyalty to the brazen policies of the Axis!"

If feelings could be intensified even more, then this happened now when the resettlement could no longer be stopped: dismay and despair, bitterness and disappointment, seized the older Gottscheers. Understandably, only few dared to express their true feelings openly. Now the certainty that a departure without return stood behind the curtain of flaming words lurked at their doorstep. Whereas the young generation for the most part accepted the resettlement as Hitler's order that had to be carried out, some of the older generation intensified their resistance during the course of the summer of 1941 to the point of open rejection. The clergy - only six priests were still officiating - were also not of one opinion.

The church counselors Josef Eppich in Mitterdorf and August Schauer in Nesseltal and their colleagues Josef Kraker in Rieg and Josef Gliebe in Göttenitz were against the resettlement.

Heinrich Wittine in Morobitz was for it, and Alois Krisch in Altlag only wanted to decide one way or the other after his community had made its decision. The Reverend Kraker made himself spokesman for the open opposition in the Hinterland.

Still the population of the "Ländchen" did not know where they were supposed to be resettling. Even though it thus made way for all sorts of speculations, the ethnic group leadership did not specify the new settlement region. Instead it vigorously set about to make the preparations for an orderly resettlement. The "Mannschaft" offered the organizational framework. Lampeter gathered the twenty-five "Sturmführer" (local leaders) at a training camp to test their endurance and, if necessary, to strengthen it. In the meantime, after the dice had fallen, the staff

headquarters looked disapprovingly upon the political activities of the Gottscheers. South Tyrol had shown them how sensitive the Italians were in these matters. Therefore, it reduced the "training and propaganda" allotment in the budget that the ethnic group leadership had submitted to a quarter. This, however, did not prevent the actual ethnic group leader, Willi Lampeter, from holding the camp. He thereby made it clear to the participants, among others, that the opponents of the resettlement had to be silenced, at the latest, at that moment in which the

individual Gottscheer man or woman was faced with the actual decision to stay or to go. To reach this goal, every method was permissible, including psychological pressure. According to Lampeter, it was absolutely necessary that the intellectual and spiritual ties which had bound the Gottscheers until now be dissolved. This was particularly true of the strong ties to the American-Gottscheers, the dependence on the dollar that arose from this, the shipping of stylish clothing that did not fit in Gottschee, the bragging with photographs about the living conditions in the United States - none of them actually of any consequential influence.

Of much greater consequence was another incursion into the subliminal psychic realm of the Gottscheers, which was only understood afterwards. Despite all the talk, by prominent authors as well, about the "negative selection" of the Gottscheers due to the mass emigration, the rest of this people in the calciferous region remained attached to their homeland. Viewed thusly, it was a positive selection. And this psychic bond to the homeland and to traditions was now to be supplanted by a fanatical acknowledgement of the Reich. To this end, Lampeter initiated a propaganda wave in No. 25 of the Gottscheer Zeitung on July 17, 1941. First of all, he asserted that "voices against the resettlement" were making themselves heard from various sides. This feigns an overly great love of the homeland. The article goes even further elsewhere: "The decisive factor that had allowed the Gottscheers to remain German for six hundred years was not a suddenly blossoming love for the homeland which actually never was a homeland. Rather it was the awareness of being responsible for something very great, something unique, for

the living German culture on earth, the Reich."

This was a total inversion of the homeland concept. Accordingly, Gottscheers never had a love of the homeland and an awareness of their homeland in all the six hundred years of their history. They were "outposts," not linguistically in the sense of Professor Kranzmayer, but politically. That the role one thus dictated to

Gottschee did not harmonize with the historical facts was, as wished, overlooked. Not "the Reich" but the Carinthian Ducal House of Ortenburg had, for economic reasons, founded the linguistic island of Gottschee in the fourteenth century. The part "... the awareness of being outposts" is very quickly stripped of its propagandistic embellishment if one soberly confronts it with the incontestible fact that the Gottscheers did not even preserve the memory of their ancestors' place of origin. It was only re-awakened in the nineteenth century. The authors of the article also did not realize the contradiction inherent in the "outpost-awareness." If such an awareness had actually existed, then there would have been all the more reason for a love of the homeland, for ties to the soil, and for the belief in God in order to persevere for so long under such difficult living conditions. After all, 600 years are almost a third of the time that has passed since the birth of Christ.

Up to this point, one can still get the impression that the propagandists attacked the love of the homeland on their own initiative and one almost would like to grant that they did this to make the departure easier for their fellow countrymen. But they hardly thought this far. Rather, let us recall the documentation "Der Menscheneinsatz" of SS-Obersturmbannführer Dr. Fähndrich in the staff headquarters in Berlin and the visit of the ethnic group leadership Schober-Lampeter-Sturm to this office of the "Reichskommissar für die Festigung deutschen Volkstums"

(Reich's Commissioner for the Consolidation of German Peoples) in mid-May 1941. Without a doubt, they received at that time secret instructions to clear away the sentimentality of the homeland concept and the ties to the soil at the appropriate moment. The three men found themselves, if one is to comprehend their total abandonment of the "Aufbauplan" (development plan) of Volker Dick, in a kind of "Befehlsnotstand" (state of command emergency). The destruction of feelings for the homeland was to lead as well to a collapse of the sense of community among the Gottscheers. This would automatically negate the promise of the staff headquarters to resettle the Gottscheers as a unit.

At meetings and in their newspaper, the tormented inhabitants of the "Ländchen" only heard and read variations of the theme, "One people, one Reich, one Führer!"

Sometime during the summer of 1941 Willi Lampeter was named SS-Sturmbannführer (battalion commander).

Wilhelm Lampeter - Gottscheer Ethnic Group leader and SS-Sturmbannführer, (SS Major) 21.12.1941

In the end, the Gottscheer women, even though they had busily participated in the cultural work, were again condemned to carry out what the men had decided about their own and their children's fates. The uncertainty about the resettlement weighed on them still more than on the men. At the beginning of July 1941, the situation was still unclear. But even if the ethnic group leadership had decided to make the settlement region known, it could not have prevented the clarification from coming from another source. In the first half of July, a leaflet from the Communist party of Yugoslavia, written in German, appeared in the linguistic island. Essentially it stated:

"The National-Socialist leaders and their little Gottscheer leaders want to ... settle you on the soil and the farms that the National-Socialist leaders have stolen from the Slovenian farmers and workers whom they have chased away without anything. The entire resettlement is a crime against the Gottscheer people! Rightfully, the natives will view you as unwelcome outsiders, as the allies of the Fascist robbers, as thieves of another's soil and of the fruits of another's labor. The houses in which you will settle will be set on fire, and you will be struck down at every step and pursued constantly .. ."

|

|

|

|

12.04.1941,

Re-settlement Staff, Untersteiermark (Lower Styria)

|

|

|

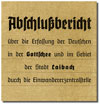

| 1.07.-27.09.1941, transport trains, numbers 1 – 33 | 03.10.1943, Final report of the EWG (Settlement Authority) regarding the expulsion/deportation of the Slovene |

A new peak of panic was the result of this unasked for "information." The ethnic group leadership could not effectively refute the propagandistic frontal attack of the Slovenian underground. They were forced to restrict themselves to strong words that did not help the confused population come to terms with the fact that the Reich intended to settle them in a region from which Slovenes had been driven.

Two Gottscheer personalities came to the foreground during this confusing period in which the resettlement date was still not known. They were the retired secondary school teacher Josef Perz in Lienfeld near Gottschee and the secondary school teacher Peter Jonke in Klagenfurt. Siding with the religious opponents of the resettlement, Perz advised his community to stay. He himself also could not decide to leave because he believed he had to draw the final conclusions from the life he had dedicated to the Gottscheer people. He was a man to whom the people

listened. His involvement in the linguistic island had begun in 1885 at the newly founded elementary school in Lichtenbach. He became a co-worker of Professor Hauffen; Wilhelm Tschinkel was his friend. He dedicated decades of his life to the folksongs, the legends and tales, and the customs. In 1920, he, like Tschinkel, had to decide whether to opt for Austria or to retire early. At that time he stayed. Wilhelm Tschinkel, however, was still too young to give up his profession.

Peter Jonke was the last native-born Gottscheer teacher at the high school in the city. He was immediately dismissed, opted for Austria, and moved to Klagenfurt. There he found a new teaching position at a high school so that he could build a new home for himself and his family. Gottschee, however, remained his main focus in his private thoughts and feelings. In numerous lectures and essays, he spoke up and fought for his homeland. He illuminated difficult historical questions, unearthed old customs, and decisively participated in bringing the Gottscheers in Carinthia together after World War II. Peter Jonke, too, felt that his fellow countrymen should stay in the old homeland, but for him Gottschee was more of a cultural than a political factor.

In July 1941, the resettlement agreement between the German Reich and Italy was worked out. It bore the heading: "Vereinbarung zwischen der deutschen Reichsregierung und der italienischen Regierung vom 31. August 1941 über die Umsiedlung der deutschen Staatsangehörigen und Volksdeutschen aus der Provinz Laibach" (Agreement between the German Reichsgovernment and the Italian Government of August 31, 1941 concerning the resettlement of the German citizens and ethnic Germans from the province of Ljubljana). The Gottscheers

only found out about this after the Second World War in a London archive. The head of the German negotiating team was not a diplomat but the chief of the staff headquarters, Ulrich Greifelt, who had been promoted to SS-Obergruppenführer. Among other things, the agreement called for compensating the resettlers for the property they left behind.

Himmler named a German "Umsiedlungsbevollmächtigten" (DUB) (a German empowered to deal with the resettlement) as administrative head of the resettlement from the province of Ljubljana. His name was Dr. Heinrich Wollert. The Italian office was held by the same "High Commissioner" Emilio Grazioli who was already mentioned earlier.

Despite the strict secrecy, rumors about the location of the new settlement region finally filtered through. That it was going to be a region that had been settled by Slovenes was evident from the communist flyer. The rumors concentrated around the "Ranner Dreieck" (triangle of Rann; in Slovenian, Brezice), with which one or another Gottscheer was personally familiar. It was located 35 to 40 km northeast of Gottschee, in the southeastern corner of Lower Styria. An energetic marcher could reach it in a day. It stretched from the Orlica mountains to the Croatian Uskoken region. Its climate is so favorable that vineyards are cultivated here. Dr. Wollert gives the following description of the region in the No. 47 issue of the Gottscheer Zeitung of November 17, 1941:

|

|

|

| "Ranner Dreieck" (Rann-triangle) | Expulsion/ Deportation of the Slovene from their homeland, 1941 | |

"What does the new settlement region of the Gottscheer ethnic group look like?"

Upon order of the Reichsführer SS ... upon the recommendation of the district leader ... of Styria the so-called Rann-triangle, a strip on the lower Sava, the Gurk and the Sattelbach (brook), has been selected for the settlement. It is a unified, self-enclosed settlement region, which is formed by a fertile river valley. Mountains and hills, on which grapes are grown, surround this region and protect it from cold air currents."

"The center of this region is the city of Rann (Brezice) ..."

As a warning, the opponents of the resettlement spread the anxiety-provoking news that the Gottscheers would receive a settlement region from which the Slovenes had been driven by force. But also those Gottscheers who had in their hearts already resigned themselves to leaving their old homeland had nightmares when they thought of themselves moving to farms that had been taken from others.

The inhabitants of the "Ländchen" realized that matters were getting serious when they saw the preparations for installing the resettlement offices in the city. Now they could also figure out that it would not be long before they had to start on the trek into the uncertain future. The DUB set about constructing a branch office, as did the DUT (Deutsche Umsiedlungs-Treuhand-Gesellschaft - German Resettlement Trust Company), whose task it was to appraise and take over the resettlement property. An office of the district leader of Styria in his capacity as district representative of the Reich's commissioner was set up in Marburg an der Drau. It was given the task of transferring the Slovenes from the Rann-triangle and installing the Gottscheers - also other ethnic Germans! - on their properties. In particular, this was accomplished by employees of the DAG (Deutsche Ansiedlungs-Gesellschaft - German Settlement Company), which was incorporated in the Marburg office of the district leader. One day, the "Sonderzug Heinrich" (special train called "Heinrich") of the EWZ (Einwanderungs-Zentrale - Central Immigration Office) rode into Gottschee, a shrewdly devised mobile office for the "Durchschleusung" (processing) of the resettlers and for the categorization according to the most diverse characteristics. The special train with the ingenious name "Heinrich" appeared wherever ethnic Germans vacated their homeland.

|

|

| Gauleiter (Province Administrator) Siegfried Uiberreither | |

In the meantime, significant difficulties developed in relocating the Slovenes from the Rann-triangle. The relevant discussions had already begun in May 1941. The relocation was to take place in three waves. The first two had nothing to do with the settling of the Gottscheers. - The just founded Croatian state had declared itself willing to accept the transferred Slovenes on the condition that it would extradite those Serbs who had settled in Croatia after World War I to the remaining area of Serbia. Hitler gave his consent to this plan on May 18, 1941. However, it could not be set into motion because the partisans in the Italian occupied province of Ljubljana had begun their resistance movement in Lower Styria and in Croatia. The Germans were not prepared for this. Himmler immediately

stopped the transfer of the Slovenes. The Croatians, however, retracted their offer to accept them. On another side, the Styrian district leader Uiberreither let it be known that he was not only against relocating the Slovenes but also against the settling of the Gottscheers on their territory. But he was not able to offer another more just solution. The staff headquarters outdid him with the suggestion that the Slovenes be transferred into the old Reich. Thus, the foreign policy dilemma was solved and they remained in charge of things.

On October 10, 1941 - the plebiscite in Carinthia had taken place twenty-one years earlier - Heinrich Himmler put an end to the interminable back and forth between the staff headquarters and the district leadership in Graz with the categorical command that the Gottscheers were to be resettled without delay.

The inhabitants of Gottschee were spared nothing. District leader Uiberreither had deliberately delayed the transfer of the Slovenes during the wrangling with the staff headquarters. Where were the Gottscheers to be settled now? Himmler's command could not simply be wiped out. This was the situation on October 10: There was not nearly enough space available to resettle the Gottscheers from farm to farm. Winter was on the way. The time pressure seemed to make any sort of orderly resettling impossible. Despite the difficulties that could be expected with regard to the people and the organization, the staff headquarters started to vacate the "Ländchen" and at the same time expedited the transfer of the Slovenes. Staff headquarters chief Ulrich Greifelt put SS-Oberführer Hintze in charge of coordinating both relocation movements. To be sure, as of November 8, 1941, Hintze's commission was called "Gleichschaltung" (political coordination by eliminating opposition).

The last ray of hope was extinguished. The Gottscheers had from October 20 to November 20, 1941 to decide whether or not they would opt for the German Reich. Everyone was forced to make the decision to go or to stay. No one could escape the decision. The Gottscheers disagreed just as obstinately now as they had in 1907. This time, however, it was not simply a matter of electing a delegate and then everything remaining as it was. The decision that had to be made now was also not comparable to the one about emigrating to Austria or to the United States. The emigrant of earlier times decided freely and only for himself. He could also stay if he accepted the living conditions as they were. When Gottscheers had left their homeland prior to this point in time, it had continued to exist.

Now make your decision, Gottscheer! However you decide, you will always be against your "Lantle"!

To pressure even the last countryman in this conflict of conscience, the ethnic group leadership seized upon the most effective method of modern political propaganda, the mass demonstration. Under the motto "Der Letzte Appell!" (the last call), about 900 "Mannschaft" members and more than 1,000 youths and girls paraded past the ethnic group leadership and the German resettlement delegate, Dr. Heinrich Wollert, on October 19, 1941. The likes of this had never before been seen in the linguistic island - a different, macabre six-hundredth anniversary closing celebration.

The opting of the Gottscheers for Germany began on October 20, 1941 with fateful punctuality.

Even before the "Durchschleusung" (processing) began, the staff headquarters received messages about disagreements in the ethnic group. It demanded a factual report from the DUB in Ljubljana. They were especially concerned about Dr. Arko. Apparently the ethnic group leadership had reported to Berlin that he was an active opponent of the resettlement and did not intend to resettle. The opposite was heard from other sources: Dr. Arko was reminding not only a few of his fellow countrymen of their duties towards Germany. To be sure, in a memorandum to the chief of the EWZ-special train in November 1941, he did accuse the young ethnic group leadership of not having adequately carried out the propaganda for the resettlement on an "emotional" basis. He probably meant thereby the all too harsh language with which they wanted to turn their fellow countrymen from their old homeland. With the expression "zu wenig seelisch" (too little emotion), the embittered ethnic politician apparently wanted to denounce the lack of emotional discretion. By the way, Dr. Hans Arko did resettle. He first settled in Rann/Sawe, and after the expulsion he was an attorney in Völkermarkt and died in 1953 in Klagenfurt.

The opting seemed to proceed without any complaints. Patiently, but not without some curiosity, those who opted for resettlement endured the bureaucratic processing procedure. Except for the former peddlers during the winters from 1934 to 1938, hardly any of the rural inhabitants had ever faced a German authority before. They found the very precise, but friendly questioning by the officials not unpleasant. They seemed to think that this was the proper German way.

The option-application was the prerequisite for everything else. The "Sturmführer" had brought the blank application to the house, picked up the completed form again, had it notarized by the Italian mayor, and then submitted it to the district representative of the DUP. The lists of voluntary resettlers that were set up jointly with the DUT were then passed on to the EWZ-special train. By the way, the personnel of the special train made two trips into the isolated regions so that those who opted to resettle were spared the walk to the city in the bad weather.

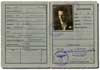

The applicants were questioned about their personal data, their domicile, the community, the district leadership office, even, indeed, about their personal attitude towards the ethnic group. Afterwards they were photographed, examined by a doctor. X-rayed, classified according to "race," admitted and made citizens of the German Reich. Of course, the citizenship papers could only be handed out, so it was said, in the "new settlement region." This was to prevent individuals who had just been naturalized from simply settling in the Reich with this document in their hands.

Afterwards, a detailed worksheet was issued for the settlement staff in Marburg an der Drau. It informed the settlement planners in Lower Styria of the profession and property of the resettler, who was given a transit number so that the local groups, villages, and hearths could be distinguished from one another. In addition,

the resettler had to make a "declaration of property." Commissions checked the claim on the site and fixed the value of the individual property. Among the numerous papers that accompanied the Gottscheer from his "Ländchen" were two that were provocatively similar: The resettlement identification papers and a declaration that he was relinquishing all his properties - house, farm, land and soil and forest - to the "Deutsche Umsiedlungs-Treuhand-Gesellschaft" (German Resettlement Trust Company).

Of course, the resettlement identity card was an administrative necessity because its possessor was in no man's land as far as his citizenship was concerned. He had lost or never received Austro-Hungarian citizenship, Italian citizenship was denied to him, he no longer had Yugoslavian citizenship, and German citizenship was only promised to him. He could not yet prove he had the latter if he had to do so. Until he finally received it, he suffered endless unmitigated psychic distress over the loss of that plot of land on which man is placed without an identity

card - the homeland.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Transport ticket

|

EWZ ticket

|

Third Reich - Re-settlers Passport

|

||

Certainly the German-Italian resettlement agreement assured the Gottscheers that they would be compensated for the property they had left behind, and they believed it when they made their property declarations. Just as surely, however, one cannot blame them for not seeing any historical parallels in this. There was, for instance, the handshake with which their ancestors had received the primeval forest land from the lord and the handshake with which the official from the German Reich received the written statement relinquishing their claim to the homeland.

We in the twentieth century hardly ever still think in symbols and emblems. This, however, does not absolve the historian from not showing them when the end of nations or tribes and established human communities is evident.

Here we have an example of such an end. A tiny part of Gottschee disappeared forever from history, a door, which had neither key nor latch, was shut with every Gottscheer farmer's signature.

Thus, the "processing" proceeded without complaints in the special train "Heinrich" but not, however, in the villages. Dr. Günther Stier, the authorized section leader in the staff headquarters surmised that the opting did not proceed as planned, although an intermediary report by Lampeter could have set his mind at peace. Only a few days prior to the expiration date for the option, he heard from the EWZ about the until-then catastrophic result: the opposition propaganda had been particularly effective in the eastern and western border regions. It came above all from the Gottscheer women and men who were married to Slovenes and was aimed at instilling fear for their lives, as well as their possessions, in those who were willing to resettle. Up to twenty-five percent of those who were entitled to opt for resettlement had not appeared at the EWZ. Similarly disappointing percentages were also reported, however, in the more centrally located "Stürme" (local groups). In Rieg and surroundings (Reverend Josef Kraker), and in Mitterdorf (Reverend Josef Eppich), a fourth of the population had likewise not come to register. Even the local group of Nesseltal still was short twelve percent, even though the Reverend August Schauer had already died on July 1, 1941. That Lienfeld, too, had a shortage of twenty percent was without a doubt due to the attitude of the retired secondary schoolteacher Josef Perz towards the resettling. However, since the "locals" of Gottschee/City, Mitterdorf, Rieg, and Nesseltal were the most populous in the entire settlement region, the undecided comprised more than a fourth of the population of the settlement region.

In Berlin, one calculated what the consequences would be if one could not bring the figure close to 100 percent in the days that still remained to the expiration date. Otherwise, the Reichs-government would be guilty of failing to live up to its agreement with Italy. The opponents, however, could claim that the Reich had forfeited its attractiveness for the ethnic Germans despite all the military victories, an argument that could not easily be refuted.

The first transport with settlers left the train station in Gottschee/City on November 14, 1941, about the same time that the staff headquarters, the DUB, and the ethnic group leadership realized the seriousness of the situation.

|

|

|

| Re-settlement of Suchen, with swastika banners | Italian Forces "Carabinieri reali" | |

The DUB received the order from Berlin to solve the problem of those unwilling to resettle as quickly as possible. Thereupon Dr. Wollert published a special edition of the Gottscheer Zeitung on November 17, that is, three whole days before the expiration of the option period. It contained an "explanation" and was quickly distributed throughout the "Ländchen." The main article made promises which could never be kept and made assertions that were simply not true. It stated among other things:

What awaits you in the new homeland? This is the question that is asked by all of those who see their friends and relatives departing without themselves being able to go along now, too.

This is the basic principle of every resettlement: In the resettlement region, the resettler receives property equal in value to the property he left behind. This means that a Gottscheer farmer who leaves a farm here that supported him well will receive a farm in the resettlement region on which he will be able to live well. It, however, also means that a farmer who had been forced by unfavorable circumstances to live on a farm that was inadequate for himself and his family will find the same in the new settlement region. It is the aim of the resettlement to create a healthy peasant class on an adequate acreage base. Thus, whoever is capable of working a farm will have the opportunity to create a farm for himself which will allow him to improve his and his family's living conditions.

The author or authors of this "explanation" had then apparently had second thoughts about the excessive promises while still in the process of writing them down. They immediately limited them again as follows:

"The selection of new farms demands the most careful preparation. The resettling staffs are most eager to take the special wishes of the resettlers into consideration. Given the significance of this task whose effects will be felt for decades and centuries, it is not possible to present the resettler with a completed solution upon his arrival. Thus, it will not always be possible to immediately settle the resettler on a property which corresponds to his capabilities and to the value of the property he left behind. On the other hand, there is no plan to set up the resettlers in camps as this could not be in the interest of the resettlers and it also would be a waste of the labor force and of time. Thus, some of the resettlers will be given property which only somewhat corresponds to that which they had up to now. The resettler can begin to work here immediately. If in the course of the winter it becomes clear that this temporarily assigned farm does not correspond to the capabilities nor to the value of the property left behind, the farmer will be relocated so that he can plow and plant his fields and finally take over and work his farm in the spring. Thus, the intermediary farms and housing may be assigned solely in the interest of the resettler in order to avoid absolutely a wrong decision which would have lasting negative effects. The author was also very aware of the concerns of the Gottscheers about the Slovenes who had been ousted from their homes because he attempted to dissipate these concerns with words that contained not a shred of truth. He wrote:

"The former inhabitants of this region have resettled in a very orderly manner and are also being taken care of by the German Reich. Besides being assured full compensation for the property they left behind, letters and reports from these inhabitants prove that they are well-provided for in their new settlement region and look to the future filled with hope."

This was pure mockery of the gullibility of the Gottscheers. The resettlement of these "inhabitants" had not been completed when the "clarification" appeared, nor could one speak of a "settlement region" of the Slovenes in the German Reich. Rather, they were in camps of the "Volksdeutschen Mittelstelle" (ethnic German intermediary office); some were employed as "Fremdarbeiter" (foreign workers) in munitions factories and then also received housing. There was no mention of about 37,000 Slovenes from the "Sawe-Sotla-Streifen," as the Rann-triangle was also

officially called, who were supposed to be and were relocated.